As shipping containers have become more common, world trade and shipping have also been revolutionized. In this blog post we will offer some very basic insights into the history of container ships, the different types of ships and the very things that actually make them container ships.

|

| Sirrah under loading at the port of Oulu in July 2012. |

What are container ships?

Container ships are cargo ships that have their dry cargo packed into standard shipping containers (TEU). Dry cargo includes the so-called bulk cargo (unpackaged materials in large quantities – grains, coal, etc.) as well as breakbulk cargo (separately packed bulk goods, barrels, moving goods, etc.). The ships have large storage spaces that are divided into cells with auxiliary rails – usually the cargo hold below the deck and/or an open floor space above the deck, where the containers are loaded onto.

Cargo holds and their hatches have been built with special attention to quick loading and unloading of containers. Until the 1950s, the cargo containers and goods were held together with sheets, tarps and lists. Nowadays the lids are solid metal plates that either have a hydraulic lifting mechanism or are opened by using the crane at the port. Only 20′ and 40′ shipping containers are loaded below the deck, whereas it is possible to easily load 45′ containers as well on top of the deck. Shipping containers that follow the ISO standards can very easily and effectively be loaded onto ships as regards the use of time and space, thanks to a detailed stowage plan.

This plan contains three dimensions – rows, tiers and container slots. A row starts at the front of the vessel and ends at the back. A tier defines the position of the container in a stack of containers. The more precise container slots are determined by their own numbers: odd numbers are on the starboard side (the right side of the ship viewed from the back of the ship, the side of the bridge) and the even numbers are on the port side (left-hand side, the side of the port). The containers in the middle have the smallest numbers, and the number increases when moving towards the sides. You can read more about the topic here.

Cargo space guides, meaning the strong metal posts built into the structure of the ship, organize the containers into straight rows and prevent them from moving when the ship rocks. The cargo space guides are also important because organizations, such as the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), demand that they exist in order to separate these vessels from normal cargo ships. In addition to the guides, the firmness of the container stacks is ensured by attaching the containers to one another using various equipment, anything from cables and chains to turnbuckles.

On most container ships the bridge and the accommodation are located near the back part of the ship, but as the TEU amount keeps on growing, some of them have been moved since 2015 closer to the front due to constrains in visibility, but also further away from the exhaust pipes.

|

| A small feeder with a crane, Mary Arctica (588 TEU) in Copenhagen in 2005. |

One special feature that some container ships have is their own built-in cargo crane. If the ship is equipped with a crane, it is referred to as ”geared”, and if not, the term is ”ungeared”/”gearless”. In the 1970s there weren’t any geared ships, and after that, they have been built by varying popularity. In 2009, only about 7.5% of container ships had a crane. The biggest likelihood of running into a crane is on a 1,500 – 2,499 TEU scale feeder, where about 60% of the ships have one. Very few of the over 4,000 TEU vessels have a crane.

The perks of a geared ship are apparent especially at ports that don’t have their own crane. However, manufacturing such a ship is more expensive than one without a crane. Recurring fuel and service costs are also significantly higher compared to ungeared ships. Also, the cranes in ports have developed to be more suitable for handling containers, so especially the cranes on old ships can’t compare with those regarding speed or efficiency.

A whole lot of things can be fitted inside a container ship that can be 400m long, 59m wide and 16m draught at maximum, so we won’t go into details about the different sections in this blog post. You can read a very detailed guide on the different parts and sections of a container ship from here.

The lifespan of a modern container ship is 10.6 years on average, which is the shortest lifespan of vessels in general use. In comparison, we can mention that the average lifespan for bulk carriers is around 16.6 years and for oil tankers around 17 years.

Different types of container ships

Container ships are divided into a couple of different size categories.

|

| Maersk Triple E Class ships are the biggest container ships (ULCV).

|

Ultra Large Container Vessel (ULCV) is the biggest of the container ship types. Ships of this type are at least 366 meters long and 49 meters wide, their draught is at least 15.2 metres. The minimum amount of containers that can be loaded is 14,501 TEU. 51 ports around the world are able to take in these massive ships. The outer dimensions of the vessel are determined by the fact that they need to fit through the Suez Canal. In 2012 there were only 161 of the ULCV type ships in the world.

The biggest cargo ships at the moment, the Maersk Triple E class ships can fit 18,340 standard containers (TEU / 20′ shipping container) at the same time. These container ships are 400 meters long and 59 meters wide – around 17 times bigger than the ships before World War II. Size-wise they can be paralleled by oil tankers and the biggest bulk carriers.

Some experts think that nowadays the biggest container ships are of the optimal size when thinking about the economical profit – if the ships get any bigger, the facilities at the port would become too expensive, the time for loading/unloading would be too big, there would be too little suitable ports and the insurance costs would skyrocket.

|

| New-Panamax ship at the port of Hamburg in 2015: CMA CGM Titan (TEU 11,400, length 363m) |

The Panamax ships have gotten their name from the fact that they fit through the locks at the Panama Canal, which are 32.31 metres wide, 294.13 metres long and 12.04 metres deep. However, a third new lock was opened in June 2016 to allow bigger ships with a size of 49 x 366 x 15.23m to pass through as well.

- New-Panamax: 10,000 – 14,500 TEU. The name refers to the fact that the ship can pass through the new locks of the Panama Canal. A New-Panamax ship can carry 19 rows of containers (12,000 TEU) and is comparable to Suezmax tankers in size (tankers that can fit through the Suez).

- Post-Panamax: 5,101 – 10,000 TEU.

- Panamax: 3,001 – 5,100 TEU.

|

| The ships spotted in Finnish ports are most often feeders. This is BF Victoria (small feeder, TEU 508) in March 2012. |

- Feedermax: 2,001 – 3,000 TEU.

- Feeder: 1,001 – 2,000 TEU.

- Small feeder: Under 1,000 TEU.

History and background

|

||

| Starvationer at the Ellesmere Port Boat Museum in the 1980s. Photo: Jack Brady Archive Collection / Bugsworth Basin |

The first standardised cargo ships were already in use in England at the end of the 18th century. In 1766, engineer James Brindley designed the Starvationer ship for 10 wooden containers in order to transport coal from Worsley Depth to Manchester through the Bridgewater Canal.

Before World War II, the first container ships were used to transport the luggage of the passengers on the Fleche d’Or luxury passenger train on the journey from London to Paris and back to London.

In the 1950s, break bulk was loaded onto ships and unloaded individually in barrels, sacks, and so on. This is when the standardized shipping containers (TEU) entered the picture, making it possible to pack around 28-85m3 / 29,000kg of goods into one container at a time.

All that can be seen from the outside of a factory-sealed container are the codes used for its tracking. Nowadays the tracking is extremely efficient – the arrival time after a two-week-journey can be predicted even within a fifteen-minute range! The seal on the lock will make sure that container is not opened before its final destination, meaning that considerably less cargo is lost/stolen. Packing the goods into containers also reduces the need to handle the goods significantly, which means that fewer goods are also broken.

Since containers have become more common, transporting breakbulk takes 84% less time and 35% less money compared to the previous methods. What once was a ship journey lasting a couple of weeks can now easily be dealt within a few days. The standardized container system did, however, require its own battle with trade unions, freighters, ports, train and ship companies and so on that lasted for a decade in order to make the system function properly and become more common. One of the things to be standardized was also the container ships designed for transporting shipping containers.

|

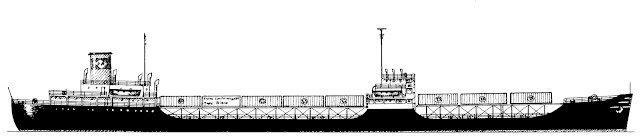

| The plan chart for an Ideal X modified from a World War II T2 oil tanker. Photo: Wikimedia Commons. |

The first container ships after World War II were T2 tankers that were modified to transport containers by the “father of shipping containers”, Malcolm McLean. The first one of these, SS Ideal X, made its maiden voyage from Newark, New Jersey to Houston, Texas on 26.4.1956. In 1957, the first ships that were deliberately built as container ships (Gateway City being the first) began operating in Denmark and between Seattle and Alaska.

|

| SL-7 ship, USNS Regulus. Photo: Wikimedia Commons |

In 1972-1973 eight Algol class cargo ships were built, in other words, Fast Sealift Seaships (FSS), i.e. SL-7, for Sea-Land Services that had previously been owned by McLean and was then run by Reynolds Tobacco Company. Nowadays it is owned by Maersk Group. With the speed of 33 knots (61km/h), they are the fastest cargo ships of all, even today. Due to their expensive operating costs, all eight ships were sold to the US navy in 1981. They were improved with cranes and more advanced possibilities for transporting vehicles, and have since then been used for example for cargo transportation at the Gulf War. Nowadays their usage is again very little.

Useful additional information on the subject:

MarineTraffic site is an excellent place to follow container ship traffic (and other ships too) in real-time based on the name of the ship or the port. In addition to this, the site contains other information about the various vessels (former names, etc.).

Shipspotting.com site will also show you the TEU loading amounts that MarineTraffic didn’t show you.

Wikipedia has a comprehensive article on the stowage plans of container ships.

Shipbuilding Picture Dictionary offers a very extensive and detailed article on the various parts and sections of container ships. There is also information regarding other types of ships available for those interested.